Acquiring a driver’s license is a rite of passage in the USA, and when I first acquired one back in the day, I never looked back (aside from the occasional state transfer requirements). That is, until I arrived in Sweden! Sweden will exchange foreign driving licenses from countries in the EEA/EU, but it does not accept those from the USA. So there you have it, Americans need to get a new license when moving to Sweden. There are several steps entailed in the process, and being an experienced driver does not forego those steps. I found the process quite enlightening in terms of what is focused on here versus in the USA. While there are certainly commonalities in driving, there are a few key points of difference that I also took away.

(Ample road signage and roundabouts help direct cars on what to expect so they can adapt accordingly)

The first point is Sweden’s attention to road safety. In 1997, the country adopted Vision Zero, a policy goal that no one should die or be seriously injured in traffic. It is an incredibly bold goal, and it has involved strong political will and a commitment to road safety. This includes setting a high bar for earning the right to drive. During my training classes and exam preparation, I learned about Vision Zero. From the instructors to the theory study, I observed a strong focus on adherence to speed limits, attention to pedestrians and cyclists, wearing a seat belt (always), and avoiding risky behavior (drinking and driving, fatigue, etc.). The consequences of not adhering to these are high. For example, if one is found driving drunk – defined as 0.2 per mille blood alcohol – then the penalty is a fine or imprisonment of up to six months, and the driver’s license is revoked, normally for 12 months. Even if the blood alcohol content is less than 0.2, if one drives in an unsafe manner, the same penalties can apply. Compare this to California where the limit is 0.8 per mille blood alcohol and the consequences are more varied, and it’s easy to understand the severity of drunken driving in Sweden. It’s simply not tolerated.

Excessive speed is also not tolerated. In urban areas, speed is significantly reduced in areas with pedestrians, usually 30 km/h (19 mph). In areas where there are many pedestrians, there is a sign for ‘pedestrian area’ whereby the speed of the vehicle should be no faster than walking speed, so between 5-7 km/h (3–4 mph). In studying for the theory test and also taking one of the risk courses, there is a lot of emphasis on speed. For example, how fast a car is moving and the likelihood of someone being killed from impact changes significantly between 30 km/h and 50 km/h (31 mph): if a car travels at 30 km/h, there is less than a 10% chance that a person hit will die. But if someone is hit at 50 km/h, their risk of fatality is 80%. A small change in speed makes a big difference and this is something emphasized repeatedly throughout the driving license process.

(Pedestrian zones require that the drivers slow down to “walking speed” to avoid potential harm to pedestrians)

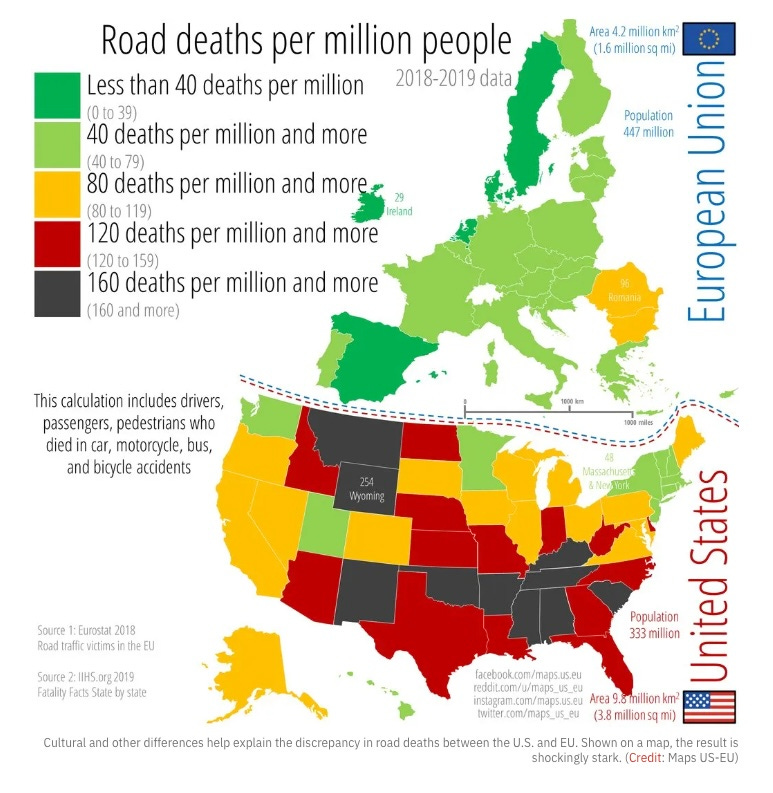

With such focused attention to road safety, Sweden has one of the best records across the EU, with 2 fatalities per 100,000 inhabitants. Comparing this to the United States, which is almost 12 fatalities per 100,000 inhabitants, it’s a stark contrast. In 2022, the total fatalities in Sweden were 227. Not yet at Vision Zero’s goal, but progress has been made. While doing research for this post, I found a noteworthy article from the Big Think on US versus European road deaths. The chart alone is fascinating.

(The Big Think article on road deaths in the EU versus the US is noticeably different. A picture speaks a thousand words.)

Another point of differentiation I observed in my drivers’ education is the focus on eco-driving. Not only is the environment highlighted in the theory study, there is a section fully dedicated to the environment on the theory test (albeit not scored as high as road safety or rules). Eco-driving is also part of the practical driving test. Many of the techniques taught are common sense, such as not idling the car and moving into a higher gear as soon as possible (especially for those manual drivers). But the biggest point highlighted for achieving good fuel economy comes from coasting rather than abruptly stopping. This also comes through in ‘planning ahead,’ which is emphasized in both the theory and the practical tests. For example, when you see an upcoming red light or when you approach a roundabout, release the gas on the approach rather than just brake when arriving. These practical tips have a big impact on fuel consumption, and also the environment. Relative to my experience in the US where no attention was given to eco-driving, Sweden integrates the environmental impacts into the driving requirements. This may be changing in the US, but it’s still a work in progress.

The final point on the drivers’ license process is the process itself. Coming in as an experienced driver, I still had to follow all the steps to receive my license. Because I came in with many years of driving experience, I know that it helped me in passing the tests. Nonetheless, I still had to do the basic requirements, which included five key steps:

It starts with the typical driver’s license permit, which entails both an eye exam and health declaration. Once you have the permit, you can drive with an approved driver, namely a supervisor from a driving school (which is what many people do) or an approved driver who has gone through an introductory training (oftentimes a parent). This is where newbie drivers get to build experience of driving on the road but only with those who have agreed to the liability entailed.

Risk 1 is a three-hour in-person course that teaches people about the effects of alcohol and drugs, fatigue and other risky behavior that should prevent you from driving a car. It involves both dialogue with the teacher and group breakout sessions.

Risk 2 is about four hours long and involves going to a physical ‘track’ to learn about speed, and how different conditions affect stopping distance (reaction time plus braking distance). On this course, we drove adapted cars to show how speed and braking is affected in icy and wet conditions – overturning and underturning. This was a fascinating experience, and one where I reflected that I only learned how to drive in those conditions when I experienced them, versus being given the chance to learn under safe training conditions.

Theory test – once you pass Risk 1 and 2, then it is time for the written exam. This exam is timed and includes 65 questions whereby 80% is the minimum score. This is not an exam you can just ‘hope to pass’ by knowing the roads. You really have to study the material and understand both the theory and the practice of driving. You are tested on five sections: vehicle knowledge/maneuvering, environment, traffic safety, traffic rules and personal conditions.

Practical test – the final step in the process is the driving exam itself. You reserve a car through the system, or use a car from the traffic school, as the inspector needs to be able to stop the car themselves should they need to. The exam is about 25-30 minutes and includes city and highway traffic, as well as country roads.

With all of these steps in the process, one feels justifiably rewarded when holding onto the driver’s license at the end! Of course, it is not so easy to pass the final two steps. In fact, the statistics show that less than half pass. My guess is that those who fail come with less driving experience overall, and thus must just go back to the books and the roads to practice. Regardless, I’m glad that Sweden takes the time to train its drivers. And for me, personally, I’m really grateful for the experience and am excited to get out to explore more of the Swedish countryside!

Very interesting Shauna! Thanks for sharing.

Did you notice on the map of fatalities/million that it is the red/Republican states that have the highest fatalities? I wonder if that is correlating with higher speed limits or something else?